Four of wisest people who have shared the planet with us agreed to be interviewed by film maker Nancy Ryley for a book. Two of the subjects, Ross and Marion Woodman, are also friends of mine and both appear in my 1981 film about Jack Chambers. My first published book review was in praise of Marion’s first book, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter (Obesity, Anorexia and the Repressed Feminine).

“In times like these,” says Thomas Berry, “…we need people who realize that we are shaping a new order of things.”

The Forsaken Garden: Four Conversations on the Deep Meaning of Environmental Illness

with Laurens Van Der Post, Marion Woodman, Ross Woodman, and Thomas Berry

[Nancy Ryley. Quest Books/Theosophical Publishing House, 1998]

This is a crucible of a book, in which the darkest truths of this dark age are articulated and examined with honesty and grace.

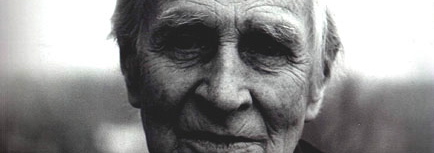

Nancy Ryley was forced to set aside her TV production career a number of years ago due to a crippling environmental illness, and The Forsaken Garden is, on one level, a book about how she turned that ordeal into a transformative journey. She has edited a series of interviews with four remarkable people: the late Laurens van der Post, naturalist, friend of the Kalahari bushmen, Jung’s biographer; Marion Woodman, Jungian analyst, bodysoul maker, champion of the feminine; Ross Woodman, English Romantic scholar, spellbinding storyteller, Bahá’í elder; and Thomas Berry, theologian, cosmologist, and dreamer of the earth.

Ryley frames the interviews with reflections on each subject’s ideas, in relation to her own concerns, her illness, and the recurrent themes of the book. Each mentor links alienation from nature to loss of soul as a way to comprehend the global ecological crisis. Each is radical and charming, learned and incisive in his or her own original way.

At first it is not clear who the book is for, and to what extent it is a personal essay about Ryley’s journey. It seems to be a Jungian deep ecology primer, with shades of Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor. Then, around 30 pages in, Laurens van der Post gets on a roll, and the book really starts to move you.

At the heart of each of the interviews is a struggle to frame the toxic overloading of the biosphere in creative breakdown/breakthrough terms. Ryley returns repeatedly to her parallel struggle to heal her poisoned body, approaching the problem of our common spiritual crisis, the diminishing of soul in the world, from several different angles. Ross Woodman tells her, “what you have is the global culture’s illness in microcosm.”

Van der Post envisions a terrible devastation of nature leading to raised consciousness, some collective maturation toward stewardship values, and regeneration in the long run. Marion Woodman echoes it in stark terms: “So long as the sacred feminine is not honored in ourselves, we will be driven to rape Mother Earth. Someday, hopefully before it’s too late, something horrendous will tear the scales from our eyes and we’ll see what we’re doing.” Dark as it is, this is not mere pessimism, but a vision that has passed through the fire of her own struggle with cancer. “…I have such faith that the planet will survive… I think that the evolution going on now … [has] never been on this planet before. Human beings have never before had to perceive the sacredness of matter in order to survive.”

Asked when people will wake up, Ross Woodman says, “I will tell you: when we can no longer breathe. When we can no longer eat. When our environment is so poisoned that cancer has become a plague, only one of many that threatens us all… then we’ll experience what a mutation in consciousness is…” Against this apocalyptic vision, he offers mental fire and the energy of love as the means to “grasp the providence that resides in the calamity.”

The cycle of conversations is rounded out by Thomas Berry’s more encouraging voice. Ryley asks him to set out the main elements of his critique of consumer culture as a “Wonderworld” that “overwhelms life with things”. He speaks plainly. “Any culture that devastates its air and water and soil, and refuses even to admit that it’s behaving in an unreasonable way, is pathological and needs to be re-invented.” Complementing Marion Woodman’s insistence that we re-inhabit our bodies, and Ross Woodman’s call to the life of the imagination, Berry emphasizes the Confucian concept of “reciprocity”, the all-species perspective: we must foster esteem and intimacy for the entire non-human world around us, on its terms, not ours.

“In times like these,” says Thomas Berry, “…we need people who realize that we are shaping a new order of things.” If this book can bring a few more of us toward that sense of humble agency and meditative urgency, it will have fulfilled its dream.