I have been visiting small art galleries in Toronto. Throughout Covid they have been sending their emails with virtual tours and videos, and occasionally I put on my mask and go downtown to be in a room, unmediated, with art. The staff are glad to see a visitor. I take my time. In the old days it would have been a rare privilege, a private viewing.

In March I invited my wife Deb to come with me to Metivier, one of my favorite galleries, which represents several artists that I love – photographers like Sabastião Salgado and Ed Burtynsky, painters like Michael Smith, John Hartmann, Greg Hardy and John Scott. I wanted to see the Smith show that was there at the time, huge abstract canvasses of dynamic colour in motion that are distinctly recognizable as Smith’s work. Smith stirs the emotions and heighten the senses the way that J.M.W. Turner or Jackson Pollock can. But I was also curious about a show of small realist paintings by an artist I had not heard of, Matthew Schofield.

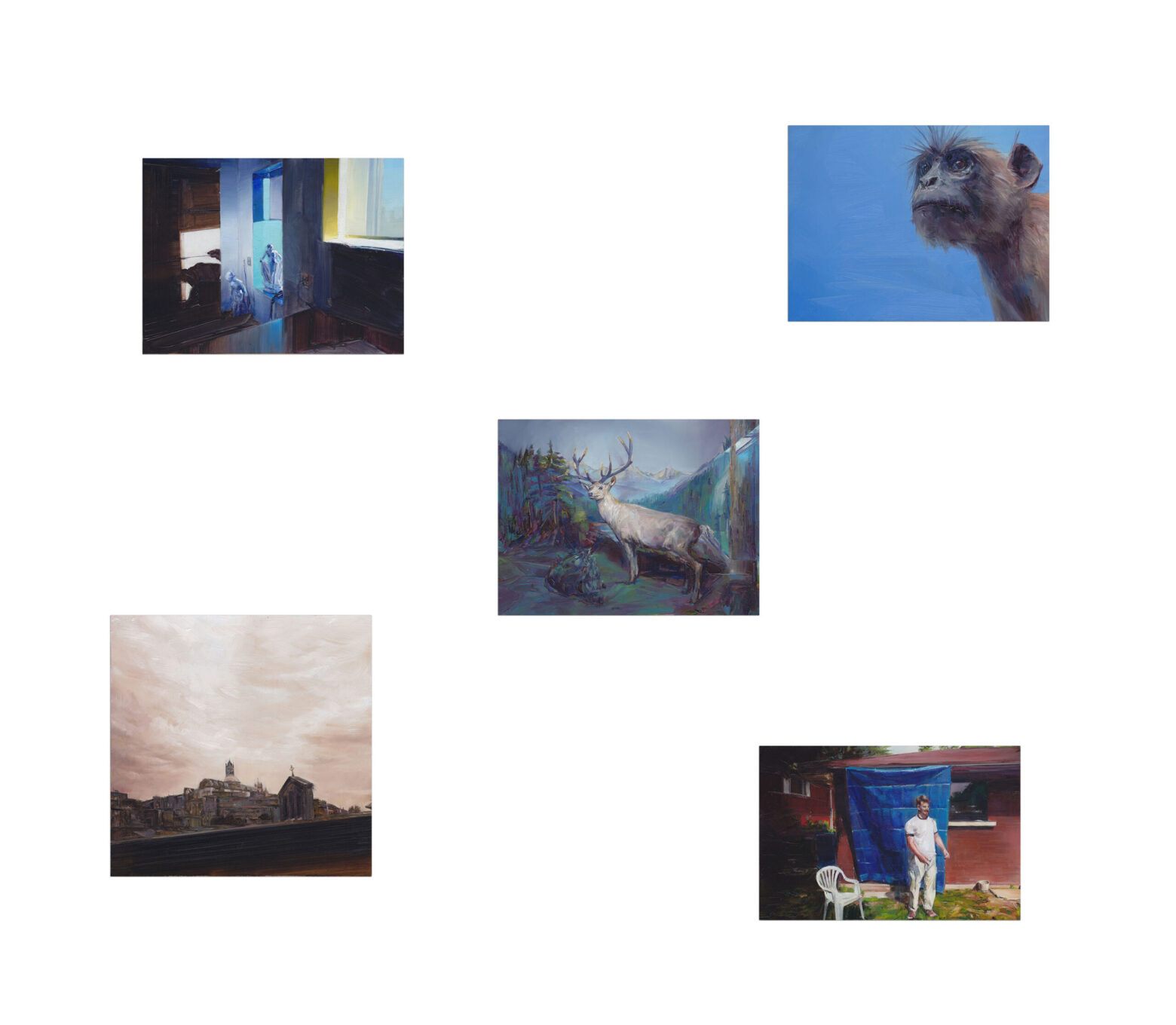

We swam slowly through the gorgeous Smith paintings, and eventually came to the Schofield show in the third room of Metivier. Even though I had read about the work, it took me some time to understand what I was looking at— not small four-by-six inch photo prints, laid out like storyboard sequences for an experimental film, but finely rendered, photorealist oil paintings. Our initial disorientation was partly due to the radical shift from the grand gestural drama of the Smith works to Schofield’s intimate miniatures.

We had to get up close to these paintings to appreciate their power. Blown up on your computer screen at home you see the brush strokes and the painterly quality, whereas on the wall they are sharply photorealistic.

The subject matter alternates between scenes of wildlife and urban life, human and non-human figures. In an empty fairground, with bits of fast food garbage like the remnants of a wild night in a song by Tom Waits, the ride structures (“The Blitzer”) are like bright spindly insects, small beneath the sky, poised as if startled by a larger creature off camera. In one grouping of images there is a vivid closeup of a bat gracefully hanging upside down as bats do, very much alive, gazing at the viewer with intense wariness. Accusing? Fearful? Thoughtful? The overall effect of these images together is foreboding, intriguing, beautiful.

The seemingly disconnected images, I realize, are having conversations with each other, beneath the surface. In a grouping of five images called “The Same Stream Twice”, each picture references water. A Paris scene like a sepia toned postcard, the left bank of the Seine; a wide deep view of a big pale blue (infrared) field edged by dark trees, perhaps in a park with mysterious rings (COVID distancing circles); a rock-strewn green landscape above the sea; a bright titanium white wooden lighthouse, low angle thrusting up in a Kodachrome blue sky; an urban fish market scene. Heraclitus’ idea, that we can never step in the same stream twice, is a clue and a key. Artist and viewer share an ambiguous relationship to externalized memories. We all have our collections of travel photos that document and freeze, outside our heads, past impressions of new places, and the heightened awareness of the ‘new’ common to travellers.

In the tradition of luminous realism using photographs, Schofield’s techniques admirably serve his originality. His palate is enticing, rich. His urban scenes are painterly rather than photojournalistic. Deborah, who is a painter, tells me that his big skies are the kinds of blue that you tend to get when you paint from photos, photos taken to capture the ‘yes’ of the clear blue firmament. Several of the skies capture magic hour, early or late in the day, which is radiant yet moody, enhanced in subtle oil paint.

Their uncanny impact goes beyond what might be achieved if this were an exhibition of quite fine, interesting photographs. As I notice the exquisite details, I have a sense of awe that you get if you have ever seen Persian miniature paintings, where details are painted with hairs drawn from the bellies of squirrels.

After I saw the show I wanted to know more about the artist and see some of his earlier work. Schofield has been working and exhibiting for twenty-five years. In the past he has used found photos, old snapshots that are haunting, often poignant fragments of everyday life. In these recent paintings, however, he works with his own photographs, adding the dimension of his own photographic choices, point of view, and technique rather than surrendering to, or channelling, the chance and anonymity of the ‘found’ photographer’s gaze.

Photography is an essential part of Schofield’s way of viewing the world. “I habitually carry a camera and react to what I see,” he says. “Sometimes it is a time of day, sometimes it is an incident, and sometimes it is behind the scene; but it is always triggered by a need to get something down. I try to capture transitional moments.” His approach to photography is reminiscent of the work of my personal photographic hero, Henri Cartier-Bresson, who called these ‘decisive moments’, images on the run.

Schofield paints on mylar, a versatile medium for oil painting that gives him the option of tracing the images from his original photos, before rendering colour and form in paint. This doesn’t detract from the originality of the work, it enables it to get where Schofield needs to go. Art will either transcend its techniques (the sum of its parts), or not. I’m reminded of Johannes Vermeer’s likely use of optical devices in the 17th century, deduced and replicated by Tim Jenison in the documentary film, Tim’s Vermeer.

Collectively, the works suggest a common experience of life constrained by powers beyond the influence of the figures in the paintings. There is a tension between nature and culture, the wild and the tame, animals and people in ambiguous landscapes and urban spaces. Schofield’s objectified animals, including humans as animals, all seem to yearn toward subjective individuality which is beyond their reach. They are mute, stuffed, embalmed, reproduced on postcards, caught in gestures of fight or flight.

Schofield’s point of view is not anthropocentric. He withdraws the projection that places humans in charge of all other forms of life, and feels the burden of the damage that humans have caused. His work seems to articulate, with humility, the view that we are one species of animal among others in the web of life.

In the dynamic between humans and animals, often in separate images but sometimes in the same frame, the point of view seems to be that of the animals. The rabbit rushing straight out of Beatrix Potter, the bright faces of the monkeys, and the pensive bat invite compassion. Even the stuffed tiger in its museum diorama seems to be straining to look at the people down the long hallway. Joe Fafard’s bronze cows, hunkered down for a storm where they lie, life size, on the lawn beneath the looming bank towers on Wellington Street in Toronto’s financial district, seem to have wandered in from the countryside. Sculpted stone panthers have fierce life in them, while humans appear to be figures in a wax museum as in one of the larger panorama paintings, “Best Behavior”.

Having read, finally, some of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time during this year of isolation, I see a Proustian thread of mortality, sensuality, and flux in Schofield. We see what we look for, and what we want to see, but if we are lucky we are astonished by something entirely new to us.

Video of the installed exhibit: Matthew Schofield

Short bio of the artist: Matthew Schofield was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1973 and currently lives and works in Toronto. He has exhibited in Canada and internationally since 1996. His work has been shown in museums and commercial galleries in Canada, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. In 2014, Schofield’s work was featured in an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Hamilton.